Problem

Many d/Deaf and hard of hearing people require sign language interpretation services when interviewing with potential employers. To provide these accommodations, employers often work with third-party agencies to acquire interpreters based on availability.

So what are the issues?

Without visibility or autonomy in the process of acquiring a sign language interpreter, d/Deaf candidates enter interview sessions feeling uncertain and anxious. They must trust that their assigned interpreter is skilled enough to interpret their conversation with the interviewer accurately and effectively.

Interpreters are assigned to candidates without considering their knowledge of specific industries or concepts. Without this shared understanding, interpreters may misinterpret candidates’ intended meaning, which could be detrimental in a job interview setting.

Design Response

Key Features

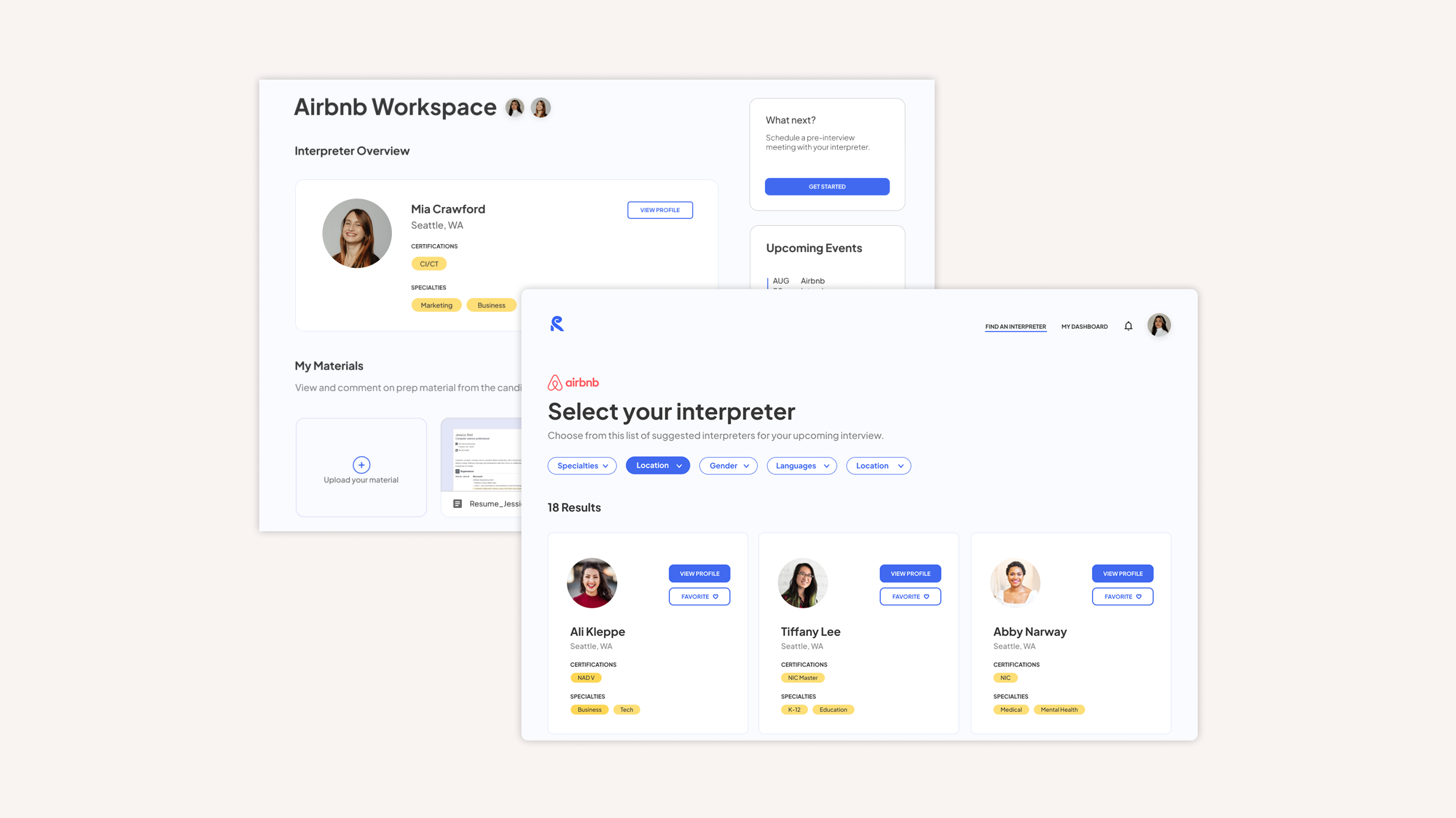

After viewing high level profile info, users can save to favorites or navigate to the full interpreter profile to send a request.

Users can navigate to the full client profile to view client introduction videos.

Candidates and interpreters can also exchange direct messages, schedule pre-interview meetings, and view upcoming events.

Research

Our initial goals for this project were to understand why many d/Deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) people struggle to find employment. We wanted to identify the common barriers the DHH community face when looking for work and how those barriers affect their job prospects.

Before conducting any primary research, we wanted to ensure that we approached our problem space from a respectful and informed perspective. As three hearing people, we fully recognized our position as people attempting to help solve a problem within a community to which we do not belong.

While under ideal circumstances, our design team would have included d/Deaf and hard of hearing people, we chose to combat these shortcomings by focusing our early efforts on learning about the community and by including DHH people throughout our research process. As we conducted our research, we carefully and intentionally chose methods to actively include DHH people in the design process and sought frequent feedback from our DHH participants.

To better understand the problem space, we started our research process by conducting a literature review and subject matter expert (SME) interviews. Through these methods, we identified some preliminary findings to help guide our research process and construct our research questions.

“DHH people historically have experienced higher rates of unemployment and underemployment… than people without hearing loss.”

Employers may be discouraged from hiring d/Deaf people due to perceived high cost of legally required accommodations, such as sign language interpreting.

Through our secondary findings we identified that the challenges that d/Deaf and hard of hearing people face were often systemic issues. To help identify the root of these issues and refine our design scope, we constructed a set of guiding research questions.

- What challenges do DHH people face during each phase of the job search process?

- Does the way in which deaf people pursue employment opportunities differ from hearing people? If so, how do the experiences differ?

- What current tools exist that help d/Deaf people when seeking employment?

- What is working/not working with the current job search and hiring processes for DHH people?

- What is currently being done to mitigate hiring discrmination against DHH people?

- How has hiring discrimination against deaf people improved or gotten worse over the years?

- What kinds of jobs are DHH people typically getting? How do these compare with the jobs they want to get?

To better understand the challenges DHH people face when looking for work, we first needed to understand their typical job search process overall.

We conducted a remote, asynchronous journey mapping activity with DHH stakeholders by having participants add sticky notes and annotations to a document we prepared and shared as a Miro board. We hoped by completing the activity alone and on their own time, participants would have the space to be more thoughtful and open with their responses.

- Understand if and how the job search process differs for DHH people

- Identify the specific activities or considerations DHH people conduct or experience throughout the job search and interview process

- Understand the process for acquiring accommodations from a potential employer

- Identify the most significant pain points throughout the process

- Understand the mental and emotional aspects of the process and how they relate to specific activities or experiences

After completing the journey map, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 11 DHH participants, 2 ASL interpreters, and 3 human resources employees.

Interviews were conducted over Zoom with sign language interpreting services and automatic closed captioning provided as needed.

Insights

We used Dovetail, a collaborative analysis and repository tool, to transcribe the recorded video interviews and code the transcripts with common themes from the interviews. To help refine the themes we identified during the tagging process, we conducted an in-person data synthesis workshop during which we grouped participant quotes and experiences by overarching themes.

Through this synthesis process, we constructed the following insights to guide our design process.

“I prefer to talk for myself because also I don’t trust the ASL interpreters to actually interpret what I’m saying accurately in a high stakes situation like job interviews that might determine my future.” - Deaf Candidate 6

“Every time I interviewed with someone, it was always a different interpreter. Right? So I had to... get familiar with the new interpreter, but it was still like, over and over and over again.” - Deaf Candidate 5

“I have to be the one to educate the recruiters and most recruiters don't know what CART real-time captioning is.” - Deaf Candidate 6

“You always have to advocate for yourself constantly.” - Deaf Candidate 2

“I did not trust the expertise of the interpreters to understand the jargon, the words we use in industry, how to communicate that feeling of confidence that I know what I’m talking about." - Deaf Hiring Manager 1

“If you have the opportunity to meet with someone before an interview, oh thank God! And meet with them for as much as you can and be like, ‘Hey, are there any words I need to know?’... Yes. We love those prep meetings. You don’t always get them though.” - ASL Interpreter 1

Ideation

Going into the ideation process, we already had been discussing the idea of a collaborative platform to facilitate communication between d/Deaf job seekers and sign language interpreters. But to keep our minds open to other aspects and potential features, we conducted an ideation workshop during which we each sketched 20 potential design concepts. We then affinity-clustered these ideas into larger concept categories.

Using our design objectives as a guide, we evaluated our concepts, eliminating those that were not robust solutions or were too speculative. We wanted our final concept to be something that our stakeholders could see as a real, possible solution.

We then recognized that many of the remaining concepts represented specific features or aspects of the platform we had been conceptualizing up until this point and could be combined into one idea. We created a storyboard to flesh out and illustrate the overall experience of the concept.

User Feedback

Next, we presented our storyboard to some of our previous research participants from our main stakeholder groups who had agreed to participate in our ongoing design panel for the duration of the project. These feedback sessions produced three main insights to consider moving forward to the prototype phase:

Participants offered suggestions for relevant profile information, including specific qualifications and types of documents they would like to see.

Participants wanted a more robust feedback feature that would help both candidates and interpreters improve, rather than relying on a simple rating system.

Participants wanted more clarity on the platform’s logistical details, business model, and discovery methods of the service.

Prototyping

We used the storyboard feedback to solidify our design concept and identify key features of the platform and a rough interaction model. We then each sketched low fidelity wireframes of key pages, combining aspects of all of our sketches to solidify the first iteration of the prototype.

We created a low fidelity prototype in Figma, which we then used to test general usability and flow of the platform.

Usability Testing

We conducted remote usability tests with five participants in order to:

- Present the lo-fi rapid prototype of the proposed design solution

- Ask participants to complete a series of tasks from both the candidate and interpreter flows

- Gather feedback on general usability of the platform

- Uncover any difficulties or areas for improvement

Using this feedback, we further refined our prototype by:

- Introducing clearer visual guidance and descriptive copy to help guide users through the platform experience

- Moving the introduction video from the workspace to the main profile page to allow users to view while browsing and aid in their selection process

Visual Design

To further refine and iterate on our prototype, we conducted a series of design workshops to establish a brand voice and a cohesive visual system that represented those values and our overall design objectives.

Since our design concept centers around the job interview process, we wanted the brand voice to strike a balance between professional and personable in a way that empowers d/Deaf job seekers to represent themselves authentically.

We chose the name “Relayt” to reflect the “relay” of information and communication between interpreter and candidate, as well as the relationship that is built as they continue to work together throughout the interview cycle.

We wanted to keep the logo streamlined and simple with imagery that mimics the R in “Relayt” and a cochlea.

Reflections

Throughout the research process, I learned the importance of choosing the right research methods in order to effectively meet research objectives and answer research questions. The journey mapping activity and interviews with DHH participants and sign language interpreters provided incredibly useful data and subsequent insights. However, the flaws in our recruitment criteria and our choice of questions for the interviews with people on the hiring side did not produce useful data or insights. In hindsight, I would have recruited only people with extensive experience hiring specifically DHH people who require sign language interpretation accommodations and chosen a method like journey mapping that identified more specific aspects of their workflow process.

While we were able to glean some powerful insights from the research we conducted, the process itself could have been more streamlined and organized. As I noted in the research section, we had issues narrowing our list of tags to a reasonable number while coding interviews. If I were to go through this process again, I would ensure that we establish a set list to work from initially and continuously check in as a team to discuss the process and reevaluate, as necessary, together.

Ideally, I would have wanted more time and resources to conduct additional rounds of testing of the high fidelity prototype with key stakeholders to further refine and iterate on our prototype.

Since we are not members of the Deaf community, it was really important to us that we approach this space thoughtfully and that we listen and learn from our participants’ experiences. Additionally, continuing to involve members of the Deaf community and sign language interpreters throughout our process was crucial to our ability to create something that met our design objectives and the needs of those we sought to help.

This whole project was an exercise in refining and narrowing. From the beginning, we were approaching a space with so many variables and systemic issues that seemed incredibly daunting to try to design a solution for. Along the way, we had to figure out where to focus our attention based on our research and project constraints to create an effective design.